“How fast can you write a show?” he bluntly asked after shaking my hand. “When do you need it?” Lee and I joked in chorus without thinking. But it was a serious question that came from producer Don Gregory on a hot summer Manhattan day as we stood in the doorway of a plush suite in the Waldorf Towers. So began the longest hurry-up-and-wait musical ever conceived.

On my way to that first meeting I kept wondering what kind of morons were making a musical about a man who was famous for being silent.

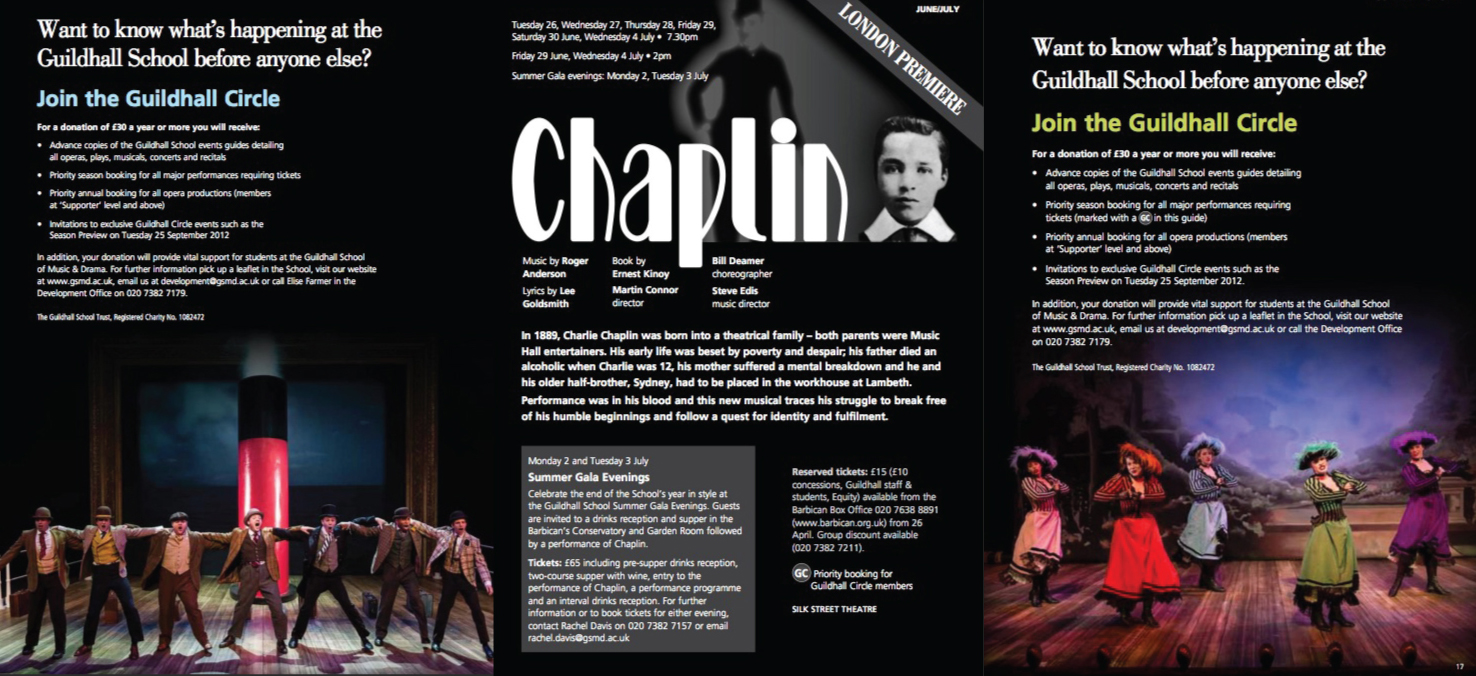

As the story goes, Broadway producer Don Gregory and the inimitable [insert other adjectives here] Anthony Newley had decided to collaborate on a musical about Charlie Chaplin; Newley was to write and direct the show. Soon, ego loomed and Newley decided to star as Chaplin as well. Don wisely nixed that notion and a war of musicals commenced.

Newley stormed off to create his own vehicle featuring an age appropriate Chaplin he could play, as well as explore the later period of Chaplin’s life when politics and the dark side of Hollywood gossip ruled. Convinced that would interest very few, Gregory hired Ernest Kinoy to create a script about a young Charlie, haunted and vulnerable.

Kinoy had Broadway credits and was a highly regarded screenwriter who recently had been praised for his work on the Roots miniseries. Lee Goldsmith also had Broadway credits and had worked with Fred Ebb and Paul Klein early on. Lee was also respected for his scripts to DC Comics Green Lantern, Flash and Wonder Woman. Both Ernest and Lee were theater historians and Anglophiles.

I, on the other hand, was a new little lamb in the Broadway woods. I had one large musical under my belt and it was yet produced. But Rodgers & Hammerstein had just acquired it (a first at the time) and William Morris had taken us in. Still, Dixie boy Anderson had never seen a Chaplin movie in its entirety. I had never been to England. Shouldn’t someone British be writing this? But I did have a background in opera as well as other period music and had recently learned to explore the “give-em-a-bouncy-C” side of my vocabulary.

Our assignment was not to reproduce Chaplin’s movie magic, but to tell how it came into being; to chronicle the creation of The Tramp, not what became of him.

There was no script to read that day, but Ernest began explaining details of plot and whimsy that would guide the concept. Act One is England, Act Two is America. Specific Chaplin film moments would be subtly pre-referenced in stage numbers as biography. Spectacularly funny and intelligent, Kinoy continued adding hints of psychology and mentioning authentic period songs that might help us. He was just revealing the stunning commedia dell’arte connection when Don suddenly interrupted. “I want a tune like ‘Smile’,” turning to glare in my direction. “When can I hear it?”

My thoughts were fixed on the fact there wasn’t any food in these swanky digs. I thought we were going to have lunch. I told them I’d take a walk and come back in an hour with the tune.

Don Gregory loved the bittersweet little melody and Lee quickly matched it with the simplest lyric he ever wrote. Years later, Chaplin’s daughter saw the show in a smaller revised version in Miami and admired it a lot. At dinner, I nervously asked specifically about the little tune that now weaves through the evening; would her daddy approve? She smiled and whispered, “He would recognize it.”

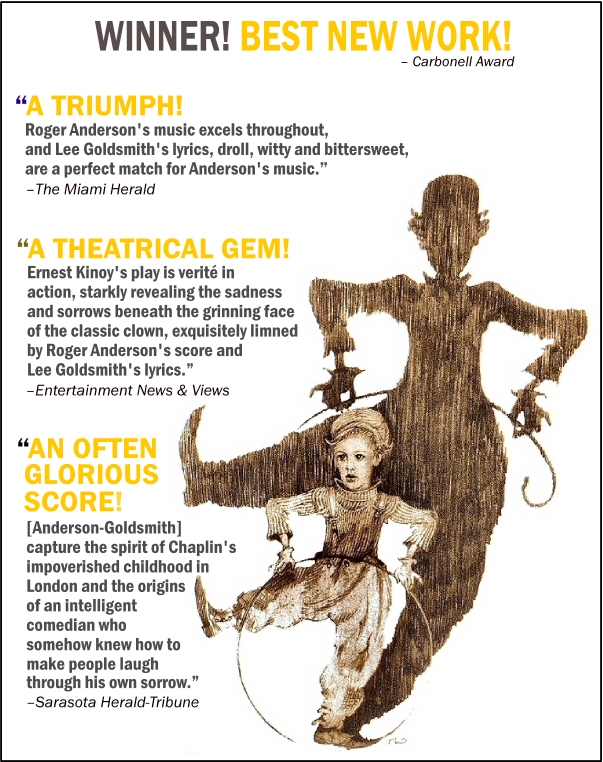

As the score grew under the guiding hands of Joe Layton and Wally Harper, it became more and more challenging. Never overt pastiche, but feeling authentic, the musical numbers travel from 1889 England to 1915 America, all with the sensibilities of a Broadway show of 1982. Go figure. All I know is I wanted to honor Charlie’s musical ingenuity by using as much of my own as I could muster. It was fun. And, best of all, I am forever young in that score.

Though we never made it to our Broadway opening night, neither did Anthony Newley. After Oona Chaplin’s death in 1991, there appeared many bio-projects about Charlie, including a pop concept recording, a play or two, a bio-tuner or two or three, a British television series, and a major film. And then, of course, Cirque du Soleil exploded onto the world stage and gloriously reminds us of all things Chaplinesque.

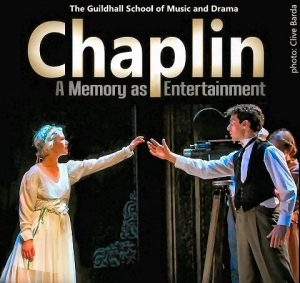

But ours is the Chaplin entertainment most don’t know — a young unknown Charlie on a fanciful adventure through time and memory on an ever-changing theatrical stage of his own making, searching for answers to his past and his future.

And we knew early on that the play must end when The Little Fella arrives; only the arrogant or foolish tread in that territory. Afterall, Charlie is watching.

More info, perusal script and piano/vocal score request at chaplinthemusical.com